Legislation introduced in state Legislature in 2006

Senate Bill 1061, proposed H.D. 1, is apparently dead

Introducer: Ihara

Held over from last year

After numerous groups and individuals testified, the House Judiciary Committee deferred action on the bill.

Chairwoman Sylvia Luke said the deferral would be to a concurrent resolution to set up a study of the Sunshine Law by the University of Hawaii Policy Forum with participation from many openness advocates.

Measure would have restricted political donations from lobbyists, but House Judiciary Committee wants to amend the measure to convene a task force that would examine ther Office of Information Practices procedures and compliance. Task force members would be eight government agencies -- including the Honolulu City Council and Kauai County Council -- winners of the Press Club Lava Tube award --and seven people selected by the Senate president and House speaker.

The Honolulu City Council and Kauai County Council have continually defied opinions by the Office of Information Practices and have taken on a campaign to get political oversight of the independent agency.

Here is the chapter's testimony:

March 21, 2006

Sylvia Luke, chairwoman

House Judiciary Committee

State Capitol

Honolulu, HI 96813

Re: S.B. 1061, proposed H.D. 1

Rep. Luke and Committee Members:

We thank you for delaying the hearing on this measure so the public could review the proposed H.D. 1 and prepare testimony.

We oppose this bill. We can see no need for it.

This bill appears some government agencies’ retribution against the Office of Information Practices for doing a fair job of determining open meeting questions.

The bill suggests confusion on the part of government agencies. The only legitimate confusion would be resolved by passing HB 2404 (pending in Senate Judiciary Committee) to clear up questions by neighborhood boards and task forces.

We suggest that any other confusion rests in the minds of people who want to conduct meetings a particular way but cannot because it would violate the law. We suggest that there are other approaches they can take.

The attorneys for the Honolulu City Council repeatedly said that a ruling against one-on-one serial communications as a vote-gathering mechanism would disrupt day-to-day operations and create inefficiencies. Judge Eden Hifo studied their arguments and found no validity to them.

But if you feel you must create such a task force, we have numerous points that should be considered so that the task force is not so overwhelmingly biased in favor of government and against openness. As you well know, this is the public’s law and there are no openness advocates on the task force. Also the task force is automatically weighted in favor of government with eight agencies represented against six appointed by the Senate president, House speaker and governor and the OIP director. We have little confidence that all six appointees will be openness advocates. Even if they are, government is overrepresented.

This bill allows the "regulated" to set the regulations.

If there has to be a task force, membership should be divided evenly between government agencies and openness advocates with the OIP director as the chairman.

The OIP is a referee and does not favor one side or the other. It has made studious examinations of the law and come up with fair recommendations and has been upheld by at least one Circuit Court judge. The governor, Senate president and House speaker should be allowed to appoint a number of task force members equal to the number of government representatives from a list of candidates submitted by the League of Women Voters.

We have trouble with placing the task force under the judiciary. The court administration has little if any knowledge or experience with the Sunshine Law. We believe the task force, if it is needed, should be attached to the Lieutenant Governor’s Office.

We question why all four county councils have to be represented. Why are their views any more important than other government boards and commissions?

Two of the councils – the Kauai County Council and the Honolulu City Council – have openly thumbed their noses at the Office of Information Practices. Their actions were so notable that the Big Island Press Club gave them the Lava Tube Award. It took a lawsuit at private nonprofit groups’ expense to force the City Council to comply with the law. These councils have pending gripes with OIP and should not be on such a panel.

For many years, officials didn’t say a word about OIP – when it didn’t tackle issues. Now when the agency is doing its job, we hear complaints.

If this passes, it would be the second time that the Legislature tried to overturn a court decision won by openness advocates.

Please stop this assault on the public interest.

Regards,

Stirling Morita President

Hawaii Chapter

Society of Professional Journalists

Senate Bill 1062

Introducer: Ihara

Held over from last year

Requires the legislature to follow fundamental principles of the sunshine law, including conduct public hearings on legislative rules; deeming correspondence on measures to be testimony; 48-hour public notice for hearings; second and third reading votes in the order of the day; and majority vote to suspend legislative rules.

On Feb. 15, the Senate Judiciary Committee deferred action on this measure.

On Feb. 24, the Senate Judiciary Committee killed the bill.

Feb. 15, 2006

Sen Colleen Hanabusa

State Capitol

Honolulu, HI 96813

Senate Bill 1062

Chairwoman Hanabusa and Committee Members:

We like the thrust of this measure. We understand that openness of the Legislature is protected by rules, but rules can change and a law would preserve a degree of openness.

We believe public notice of hearings on bills should be given on a timely manner. We also believe that a public hearing should be held on major provisions before adoption.

We also believe that all correspondence, including a governor's message, on a bill should be kept as public record of that measure.

We also believe a public hearing should be held on House and Senate rules. Also suspension of a rule should be backed up by a majority vote.

Agendas should contain the items to be voted on in each house.

Thank you for your time and attention,

Stirling Morita

President

Hawaii Chapter

Society of Professional Journalists

![]()

House Bill 2218

Introducers: Berg, Stonebraker

Senate Bill 2876

Exempts neighborhood boards from the Sunshine Law

Referred to House Judiciary Committee

Here is a link to the measure:

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/bills/hb2218_.htm

![]()

House Bill 2402

Senate Bill 2365

Introducer: Say (b/r)

The Office of Information Practices may sue in Circuit Court to enforce its opinions.

1. The Senate Transportation and Government Operations Committee passed the Senate version onto the Judiciary Committee without amendments on Feb. 6, 2006

Feb. 6, 2006

Chairwoman Lorraine Inouye

Committee on Transportation and Government Operations

State Capitol

Honolulu, HI

Re:. Senate Bils 2365 and 2366

Sen. Inouye and Committee Members:

We have long waited for such changes to the laws that protect the public’s right to know what its government is doing.

Since the inception of the Information Practices Act, we have endorsed giving the Office of Information Practices the power to enforce public records and open meetings opinions. This was the one important provision that the original law was lacking.

SB 2365 gives such power to OIP to go to court to enforce its opinions, but the enforcement would be enhanced by accompanying appropriations.

SB 2366 raises OIP’s opinions to the level of decisions in regards to open meetings. This is an important measure. Very often action is needed quickly but often becomes moot because a board continues to meet in secret. Information is a perishable item – the need for which diminishes with time. If OIP is able to act quickly and make a decision, information hidden in secret meetings could be revealed in a timely fashion.

Public agencies have started to thumb their noses at OIP— in our view without cause. These bills will go a long way to stopping such refusals to follow the law.

People who believe in government openness wholeheartedly support these two bills.

2. The House Judiciary Committee deferred the measure on Feb. 7, 2006.

Here is a link to the House version:

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/bills/hb2402_.htm

![]()

House Bill 2403

Senate Bill 2366

Introducer: Say (b/r)

Gives the Office of Information Practices the power to make decisions on open meetings and records requests. It currently issues only opinions.

1. The Senate Transportation and Government Operations Committee passed the Senate version onto the Judiciary Committee with amendments on Feb. 6, 2006

Committee report is here: http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/commreports/sb2366_sd1_sscr2024

City Corporation Council's testimony opposing SB 2366

2. The House Judiciary Committee deferred the bill on Feb. 7, 2006

Feb. 7, 2006

Chairwoman Sylvia Luke

House Judiciary Committee

State Capitol

Honolulu, HI

Re: House Bills 2402 and 2403

Rep. Luke and Committee Members:

We urge passage of these two measures. We view them as fulfilling public expectation that someone is empowered to enforce the Sunshine Law and public records act.

Since the inception of the Fair Information Practices Act, we have endorsed giving the Office of Information Practices the power to enforce public records and open meetings opinions. This was the one important provision that the original law was lacking.

HB 2402 gives power to OIP to go to court to enforce its opinions. We suggest that some funding would enhance enforcement.

HB 2403 raises OIP’s opinions to the level of decisions in regards to open meetings. This is an important measure. Very often action is needed quickly but often becomes moot because a board continues to meet in secret. Information is a perishable item – the need for which diminishes with time. If OIP is able to act quickly and make a decision, information hidden in secret meetings could be revealed in a timely fashion.

Public agencies have started to ignore OIP opinions — in our view without cause. These bills will go a long way to stopping such refusals to follow the law. Private organizations shouldn’t be expected to go to court to force these agencies to comply with the law.

Here is a link to the House version:

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/bills/hb2403_.htm

![]()

House Bill 2404

Senate Bill 2367

Introducer: Say (b/r)

Allows two or more members of a board, but less than the number of members that would constitute a quorum, to discuss their individual positions relating to official board business at meetings of other boards or at public hearings of the Legislature, and to attend and participate in discussions at presentations, including seminars, conventions, and community meetings, that include matters relating to official business. Effective 7/1/2050. (SD1)

The bill is pending in the Senate Judiciary Committee.

You can view a copy of the bill at:

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/bills/hb2404_sd1_.htm

Feb. 7, 2006

Chairwoman Sylvia Luke

House Judiciary Committee

State Capitol

Honolulu, HI

Re: House Bill 2404

Rep. Luke and Committee Members:

We ask you to kill this bill. It carves out yet another exception to the government open meetings law and creates more nondisclosure in a law designed to open up the government for the public.

Board members can discuss their personal feelings about business anywhere, anytime.

We believe this provision could be abused.

We believe the second provision is not needed. Board members could go to a session and discuss their own personal opinions, rather than make a decision. They could even consider holding a joint meeting in the public’s eye or a meeting right after the other session.

Here is a link to the House version:

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/bills/hb2404_.htm

![]()

House Bill 2977

Senate Bill 3145

Grants a new exemption to the open meetings law for a board or commission to consult with its executive director or executive secretary.

![]()

House Bill 2985

Senate Bill 2657

Introducers: Say, Bunda (b/r)

Creates a board to hire and fire the director of the Office of Information Practices.

Here is the link to the House version:

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessioncurrent/bills/hb2985_.htm

Feb. 24-25, 2006

The First Amendment in Crisis,

a Freedom of Information forum

at the William S. Richardson

School of Law

Full text of keynote address by

Tony Lewis

Ladies and gentlemen, it is an honor and a pleasure for me to take part in this conference on the First Amendment in Crisis. I cannot think of a happier place to be in crisis, or a more impressive group of conferees.

I am going to begin with a story that may not at first seem exactly in point. It is about the largest-selling daily newspaper in the world, Rupert Murdoch’s British tabloid, the Sun. And what it did to Elton John, a rock singer. I remind you that John was a favorite of Princess Diana’s, and sang at her funeral in Westminster Abbey.

On Feb. 25, 1987, the Sun printed a story that began "Elton John is at the center of a shocking drugs and vice scandal involving teen-age ‘rent boys,’ the Sun can reveal today." "Rent boy" is British journalese for male prostitute. The story gave as its source on "Graham X." The next day, Graham X was the source for a story saying: "Kinky superstar Elton John loved to snort cocaine through rolled-up $100 bills." Mr. John denied both stories and brought two writes for libel. The next day’s Sun headline was: "You’re a Liar, Elton." And so on through another dozen stories over the next months. During this time, we now know, the Sun was paying Graham X – his real name was Stephen Hardy -- $400 a week and taking him and his girlfriend to Marbella, a chic seaside resort in Spain, for an extended vacation. The last attack on Elton John, published Sept. 28, 1987, was headlined "Mystery of Elton’s Silent Dogs." It said Mr. John had had his "vicious Rottweiler dogs" silenced by a "horrific operation." Mr. John sued again: his 17th libel action since the start of the Sun campaign against him.

For some reason, perhaps because the English like dogs, the last the suits, the one about the nonbarking dogs, was scheduled for trial first on Dec. 12, 1988. It turned out that Mr. John’s dogs were not Rottweilers and did bark. It also turned out that Stephen Hardy, alias Graham X, had made up his tales of vice at the Sun’s urging. "I’ve never even met Elton John," he said later. "In fact, I hate his music."

The morning of the scheduled trial, the Sun carried a two-word headline: "Sorry Elton." The story said that the Sun had settled all the libel actions by paying Mr. John 1 million pounds in damages – about $1.7 million – and about half as much again in lawyers’ fees. The story said: "We are delighted that the Sun and Elton have become friends again, and we are sorry that we were lied to by a teenager living in a world of fantasy."

What is one to say about behavior like that? I know of only one explanation. Rupert Murdoch is said to make a profit of 1 million pounds a week on the Sun.

Now why did I start off with that tale? To remind you that the press is not always a noble hero. Of course, there is nothing as vicious or contemptuous of the truth in American newspapers or television or radio or the Internet, is there? Not in extremist talk shows? When Ann Coulter says that it would be wonderful if a bomb went off at the New York Times, she’s just kidding, right?

Well, ladies and gentlemen, you do not have to be respectable, much less noble, to enjoy the freedom of speech and press guaranteed by the First Amendment. That is one lesson, a lesson often overlooked of the first Supreme Court decision protecting the press: Near v. Minnesota in 1931. Near was Jay M. Near, who put out a weekly paper, the Saturday Press. It could politely be called a scandal sheet. And it was viciously anti-Semitic. The theme it most often sounded was that political leaders in Minnesota were in league with a group of Jewish gangsters and that the police were doing nothing about it. Minnesota had a unique law calling for the suppression of malicious journals, and it was invoked to put Jay Near out of business. The Supreme Court, by a vote of 5-to-4, said the suppression was a prior restraint especially disfavored by the First Amendment. The dissenting opinion, by Justice Butler, had a footnote giving an example of Near’s anti-Jewish diatribes. It is too nauseating to read.

You might think that the public weal suffered no injury by the disappearance of the Saturday Press. Perhaps, the late Fred Friendly thought that when he began writing a book about Near v. Minnesota. Friendly – you can see him portrayed by George Clooney in the movie "Good Night and Good Luck" – went from CBS Television to be a vice president of the Ford Foundation. One day, he was at a lunch there, and he told his companions about the book he was working on. Irving Shapiro, the chairman of the duPont Co. And a member of the foundation board, came over from another table. "Are you writing a book about the Near case, Fred?" he asked. "I knew Mr. Near." And he told this story.

Irving Shapiro’s father, Sam, owned a dry-cleaning store in St. Paul. One day a group of gangsters came in and demanded that he pay protection money. When he said no, they sprayed acid on the clothes hanging in the story, doing $8,000 worth of damage. Irving, a young boy, watched. The establishment newspapers reported the attack but did not name the gangster mob; and they did not follow up the story. But Jay Near came to the store, talked with Sam Shapiro, published a full story in the Saturday Press and campaigned against the gangsters. They were arrested and prosecuted. So Sam Shapiro did not think that Jay Near’s newspaper was worthless. And neither, incidentally, did Col. Robert Rutherford McCormick, the splenetic owner of the Chicago Tribune, who noticed the case when no one else did and provided his lawyer to take the case to the Supreme Court and argue it there.

The year of the Near decision, 1931, was the start of what has been an enormous expansion of the reach of the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has interpreted it since then to protect political speech of even a revolutionary character; anything goes, unless it is intended to bring about immediate violence and is likely to do so. Art of all kinds – books, movies, painting – is now protected. The press is almost completely free to bare the secrets of government, and the secrets of the bedroom, without fear of penalty. There is almost no chance that anyone can stop the press from publishing what it wishes, even when the government claims that it will menace national security.

Freedom of expression is broader in this country than any other, including some countries that we think of as like ourselves. In Britain, for example, the government would almost certainly have gone to court to enjoin publication of stories like those in the New York Times about warrantless wiretapping. And it would have got that injunction. Libel law is stricter than ours. Britain’s courts have declined to adopt the rule of New York Times v. Sullivan, and it is not followed in any other country.

Not only do we have more freedom than others, we have more than we had in this country at any time in the past. So why are we talking about "The First Amendment in Crisis"?

In my view the greatest threat to free discussion of public issues today is not prior restraint but official secrecy. We have the most secretive federal government in American history. After the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Attorney General John Ashcroft ordered thousands of aliens arrested and detained for weeks and months. Their names were kept secret, their places of imprisonment withheld even from their families. Just this week, we learned that the Bush administration has a large program to reclassify documents that were declassified and have been on open library shelves for years.

But my guess is that the principal concern here is over subpoenas to journalists, requiring them to testify before grand juries in criminal investigations or to testify in discovery or trials in civil cases. The case of Judith Miller is surely on everyone’s mind. She spent 85 days in prison for contempt after refusing to name her sources to a federal prosecutor looking into how the name of Mrs. Valerie Wilson, a covert CIA official, was leaked to the press. Other cases are pending. In one, reporters have refused to answer questions by lawyers for Wen Ho Lee in his civil suit against the government for, as he sees it, smearing him as a spy for China in leaks to the press.

The claim made by Judith Miller, and made generally by the press and its lawyers, is that the First Amendment gives journalists a constitutional privilege against having to testify when they are asked to name confidential sources. The argument is that use of such sources is essential to meaningful journalism, and they will dry up if reporters violate their promise of confidentiality and testify. Now I want to subject that claim to hard-headed scrutiny. The first thing to say is that the claim was squarely rejected by the Supreme Court in 1972 – in Branzburg v. Hayes, as you know. Some lower courts have found reasons to immunize journalists despite Branzburg. But the Supreme Court has never changed its mind, and in my opinion, there is zero chance of the court’s doing so.

Why do I say that? First, because freedom of the press has been protected historically almost entirely when a publication is penalized, for example in libel cases, or when there is an attempt at restraint before publication. The Supreme Court has rarely protected the press when it seeks to acquire news. It has done so only in the context of open courtrooms. And the basis of the press privilege claim is that it is needed to acquire news.

Second, there is the question of who is a journalist. In the Branzburg case, Justice White said freedom was just as much for the "lonely pamphleteer" as for the established press. And now we have 27 million lonely pamphleteers, self-nominated journalists publishing their blogs on the Internet. (That is the latest estimate of blogs, published last weekend in the Financial Times.) Are they to be protected against subpoenas when they come up with a scoop, as some of them do?

I think the interest of the press in this area has to be balanced against others. The citizen whose life has been ruined by false and damaging stories attributed to unnamed sources should not be left without a remedy. Think of Wen Ho Lee. Or go back to the case in which a constitutional privilege was claimed for the first time. The case was called Garland v. Torre, decided by the U.S. Court of Appeals in New York in 1958.

Garland was Judy Garland. Torre was Marie Torre, a television columnist for the New York Herald-Tribune. She published a column saying that CBS executives had told her they would no longer use Judy Garland on the air because she was too fat and too drunk. Garland sued and demanded the names of the alleged CBS sources. Torre refused to give them, and made the constitutional claim. The 2nd Circuit rejected it, in an opinion by Potter Stewart, then a 6th Circuit judge visiting the 2nd , later a Supreme Court justice. The journalist’s claim had to yield, he wrote, to the fundamental right of Americans to seek justice in the courts.

I spoke just now of Marie Torre’s alleged sources. Let me describe another case to show why I did. It arose years ago in South Africa, in the time of apartheid. A news magazine called To the Point published an article critical a black minister named Manas Buthelezi. He spoke publicly of peaceful reform, the article said, but informed sources had told the magazine that in his private circles, he called for revolutionary violence. That charge could have had terrible consequences for Buthelezi in apartheid South Africa. He sued, and demanded to know the names of the sources. The editor refused to give them. The court, rejecting a privilege claim, entered judgment with damages for Buthelezi. Thereafter, in a great scandal, it came out that the article had actually been written by the secret police – and planted in To the Point to injure Buthelezi.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr., one of the greatest friends that freedom of speech and press have ever had on the Supreme Court, once cautioned the press against crying woe.when, unusually, it lost a case in the Supreme Court. "This," he said, "may involve a certain loss of innocence, a certain recognition that the press, like other institutions, must accommodate a variety of important social interests."

I think that is a fair warning. It does not mean that the press has no reason to worry about having to disclose confidential sources. It does. I have friends in the business who face that problem right now, and I have every sympathy with them. But I think it is unwise to make overbroad claims- constitutional arguments-that ignore other interests and that will not succeed. I think it is vital to show that the facts really do threaten acute public interests.

Take the Judith Miller case, for example. It was not an example of the press performing its vital function as a .whistle-blower, exposing official wrongs. The wrong in this case was the disclosure of a CIA official’s name in order to get even with her husband, Joseph Wilson for telling us that President Bush’s claim of Iraqi purchase of uranium ore in Africa was false. What is the public interest in protecting the author of that nasty business?

The example that to me really shows the need to protect the press’s use of confidential sources in the

reporting in The New York Times about President Bush’s secret order to the National Security Agency to conduct warrantless wiretapping. the stories, by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau, disclosed a presidential action that violated the law. The Justice Department has tried hard—very hard—to defend the legality

of his order. But it plainly conflicted with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which provides a system of warrants before a special court and which declares that it is the exclusive method for such tapping. The Justice Department argues that a war president has "inherent power" to ignore that law, but that proposition was definitively rejected by the Supreme Court 50 years ago in the Steel Seizure Case.

So the Time reports performed a signal public service: the sort of press performance essential to keep this a country of laws, not men. Now the Bush Administration is going all-out to investigate who leaked the facts to The Times. It may subpoena Jim Risen and Eric Lichtblau. If it does, that would present the strongest argument for protection of the reporters and their sources. The balance of interests, that is, would be for protection. How could that balance be struck? Judge David Tatel of the U.S. Court Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit suggested that the courts adopt a qualified, privilege under a statute giving them the power to define all testimonial privileges. I hope we can discuss this in the panel tomorrow morning.

Ladies and gentlemen, I have to tell you that my views on these matters are affected by something else.

I think the worst threat to our constitutional system today—to our freedom—comes not from challenges to the First Amendment, worrying though they may be, but from a relentless effort to secure unrestrained, unaccountable presidential power. The Bush Administration’s lawyers have argued not just that the president can ignore the law and order wiretapping without warrants. They have argued that he can order the use of torture, ignoring treaties and a criminal statute that prohibit it. If he says torture, they say, any attempt to stop him by Congress or treaty would be an unconstitutional interference with his power as commander in chief. They have argued that the president can order the detention of any American citizen suspected of a connection with terrorism: detention forever, in solitary confinement, without a trial and without access to a lawyer.

Those are not abstract arguments. Citizens have been imprisoned, conversations tapped, prisoners tortured. Lest you think that I am speaking loosely, let me give you an example of what has been done to detainees in Guantanamo. I warn you that it will not make pleasant listening.

One detainee at Guantanamo is Mohamed al-Kahtani. On Aug. 8, 2002, he was moved into an "isolation facility, "where he stayed for the next 160 days, his cell continuously flooded with light, his only human contact with interrogators and guards. He was questioned for 18 to 20 hours a day for 48 out of 54 straight days. He was threatened with a menacing dog. He was forced to wear a bra while thong panties were placed upon his head. He was leashed and ordered to perform dog tricks. He was stripped naked in front of women. He was taunted that his sister and mother were whores and that he was gay. Seeing Kahtani after such treatment, FBI agents concluded that he evidenced behavior consistent with extreme psychological trauma: talking to nonexistent people, reporting hearing voices, cowering in a corner of his cell covered with a sheet for hours on end.

Under the pressure of those tactics, al-Kahtani named 30 other Guantanamo inmates as terrorists. Each of them remains in prison solely because he listed them; there is no other evidence against them. That leads to another point about the detainees. Two recent studies have found that most of them were not members of al-Qaeda. They just happened to be in the wrong place when sweeps for possible terrorists were made. Or they were turned over to the United States by Afghan warlords who were given a large bounty for every such prisoner.

34 detainees have been killed in American prisons in Iraq and Afghanistan, some of them tortured to death. In only 12 of those cases has anyone been punished, the longest sentence was 5 months in jail for an Army sergeant who killed an Afghan prisoner.

Two years ago, the Supreme Court held that the Guantanamo detainees were entitled to seek writs of habeas corpus, challenging the reasons for their imprisonment, in United States courts. In an effort to stall off judicial examination, the Defense Department installed a system of what it called Combatant Status Review.Tribunals. It holds hearings, but the detainee who appears before one has no lawyer, and almost all

the evidence is secret. The legal adviser to the tribunals, a Navy judge advocate general, Commander James Crisfield, has said that the tribunals almost entirely rely on "hearsay evidence recorded by unidentified individuals with no firsthand knowledge of the events they describe."

And Congress passed a bill sponsored by Senator Lindsay Graham that strips the courts of jurisdiction

to hear habeas corpus cases from Guantanamo. If that statute is upheld by the Supreme Court, it will mean that no court can look into what goes on in Guantanamo.

I have gone a long way from the subject of this conference, ladies and gentlemen; but I do not apologize for that. It is always good to keep things in proportion.

The author of the First Amendment, James Madison, thought its great function was enabling the press to, as he famously put it, "examine public characters and measures." When we talk about the press and the First Amendment today, not only point to legal threats to the press but consider how well the press has been performing its high constitutional function. Over the years since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, how well has the established press done in alerting the public to the concentration and abuse of power in the White House? How hard is it working now to report the realities of what is going on in Guantanamo?

After 9/11 there was, I think, what could be called a paralysis of the will. The New York Times and The Washington Post actually apologized to readers for their timid performance in the run-up to the Iraqi war—their failure to look more closely at the reasons given for the war, reasons that turned out to be false.

Until the NSA wiretapping exposure, I do not think our great newspapers would have won an accolade from James Madison.

Let me end with a quotation from an opinion in one of the greatest victories for the press, the Pentagon Papers Case. You will remember that the Government tried in 1971 to stop publication by The Times and then The Washington Post of a secret history of the origins of the Vietnam War.

The Supreme Court rejected the government’s argument. In a concurring opinion, Justice Hugo L. Black wrote; "In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. . . . The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and. inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell. In my view, far from deserving condemnation for their courageous reporting, The New York Times, The Washington Post and other newspapers should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly. In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam War, the newspapers nobly did precisely that which the Founders hoped and trusted they would do."

That is the vision of the First Amendment in which I believe: a restraint on government and a responsibility on the press.

Confidential Sources

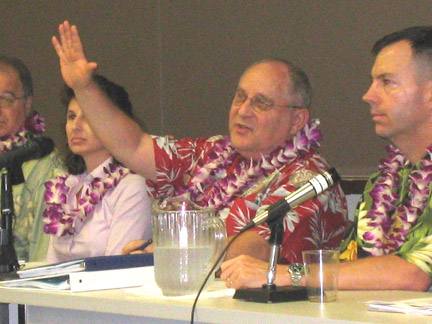

Panel members Honolulu Prosecutor Peter Carlisle, author

and former New York Times columnist Tony Lewis

and Honolulu Advertiser investigative reporter Jim Dooley.

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press has found more than 460 criminal cases sealed from public view in the federal court in Washington, D.C.

Reclassification of government documents to take them out of public view is running under full steam, Freedom of Information requests are dramatically up and more federal subpoenas have been issued this year than in the 1970s, says Executive Director Lucy Dalglish.

No wonder she says it has been "a disappointing year."

The Bush administration "controls the message ... Control and secrecy are their mantra," she told a Freedom of Information forum Feb. 25 at the William S. Richardson School of Law.

Not only are subpoenas increasing, but confidential sources have been under the national microscope due to the leak about Valerie Plame, wife of an administration critic.

Dalglish says the debate over confidential sources comes up every generation and no one seems to learn anything from it.

In 1973-79, there were 99 bills in Congress to protect unnamed sources of reporters, "but the media couldn’t decide what they wanted."

Author and former New York Times columnist Tony Lewis said he is troubled that the media would demand "protections that other people don’t have."

However, he said, it has come to the point that some sort of protection is needed.

But Lewis repeated his comments that it should not be applied across the board but should be granted in cases where the media do their constitutional function of uncovering secrets of government.

Freedom of Information

Panel members: state Sen. Les Ihara, Honolulu Advertiser Editor

Saundra Keyes, University of Hawaii journalism professor

Beverly Keever and FOI attorney Joe Steinfield of Boston.

FOI Nationally

If there is a criminal proceeding and no reporter knows about it or can cover it, there is no press coverage. Then there is no public knowledge, then there is no democracy.

Boston media attorney Joe Steinfield says that was the vision of the Founding Fathers.

"The right to gather the news is as critical today as it was at any time in our memory," Steinfield said at an FOI forum at the University of Hawaii law school.

But the right to gather the news is a relatively recent development – through court decisions about court access, he noted.

It wasn’t until 1980 that the U.S. Supreme Court (in Richmond Newspapers v. Virginia) said the public has a right to attend criminal trials.

Then, the high court followed up with decisions involving the Press-Enterprise – one requiring open sessions of jury selection and the other saying pretrial hearings are public.

(These are detailed in Steinfield’s position paper. Click here to see the paper )

FOI Locally

More than 30 years ago, there was no right to access Hawaii government, local media law expert Jeff Portnoy says.

Then Watergate occurred in the early 1970s, and governments across the nation started granting access to the public and the media, he said at a Feb. 25 forum.

But what ever the Hawaii Legislature can give the public, it can also take it away.

Take for example, attorney Portnoy says:

UH journalism professor Beverly Keever said openness "is not as extensive as it was 30 years ago" before enactment of the state Sunshine Law.

Even 20 years ago, the media and public were "clamoring for records" such as government loan documents, lists of who is in prison and eligibility lists for Hawaiian Homes leases, she said.

But now "the rise and fall" of the Office of Information Practices, which has called for more openness in various opinions, may be coming. OIP has had "trouble getting its opinions to stick," she said.

And private organizations have to sue to enforce OIP’s opinions. "OIP cannot make Hawaii government open by itself," Keever said.

The OIP has lost staff due to budget cuts over the years. The governor should "reinvigorate that office," she said.

Prior Restraints

Law school dean Avi Soifer, Massachusetts Chief Justice

Margaret Marshall, U.S. District Judge David Ezra

and University of Hawaii Journalism Chairman Gerald Kato

talk about prior restraints.

Gerald Kato says news technology moves so fast that any attempt by government to block publication may be a thing of the past.

"Technology allows you to just put something online and not tell anyone," the chairman of the University of Hawaii journalism department told a Freedom of Information forum Feb. 24 at the UH law school. "As a practical matter, there’s nothing the judiciary can do to stop you."

But someone could take after-the-fact action such as a defamation suit or impose some sort of penalty.

Kato was a panelist on prior restraints – government actions that impose a complete prohibition on dissemination of a fact or information.

Kato said he sees a different kind of prior restraint occurring – where government blocks release of information, such as sealing court records or closing meetings.

Panelists agreed that prior restraints are pretty much a thing of the past because the case law is well-established and the government has a heavy burden to block publication.

U.S. District Judge David Ezra said Hawaii has had a few laws "designed to keep; information away from the public."

He overturned two such laws:

UH law professor Jon Van Dyke said the term prior restraints is misunderstood.

Prior restraint means government action that puts a complete prohibition on the dissemination of information, such as the Pentagon Papers or Progressive Magazines story on how to build a hydrogen bomb, Van Dyke said.

There are other types of prohibitions that are not prior restraints, such as injunctions, including restrictions on abortion protesters, he said.

Military Access

Military access panel: attorney Eric Seitz; Kayla Rosenfeld,

news director at Hawaii Public Radio; attorney Jay M. Fidell; John Schum, attorney

for Marine Corps Base Hawaii at Kaneohe; and Gregg K. Kakesako,

military writer for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Defense attorney Eric Seitz says the military tries to control access to courts-martial and other proceedings to keep things under wraps.

Officials may move military trials to remote locations, close hearings and don’t readily disclose a schedule of the proceedings, he said.

The military structures the hearings "to the point of orchestrating and controlling the environment," Seitz said at an FOI forum about access to military proceedings..

"They don’t want publicity to come out about their cases," he said.

Star-Bulletin military reporter Gregg K. Kakesako said the military is "very structured" and "a different culture."

If a reporter doesn’t know the right question to ask, he or she will not get the sought-after information, he said.

Reporters have to rely on a public information officer to learn of courts-martial or hearings similar to grand jury proceedings, he said.

Panel members also keyed in on the court of inquiry held after the submarine USS Greeneville smashed into the Ehime Maru, a Japanese fishing training ship, killing nine people.

Attorney Jay M. Fidell said 400 reporters had to be selected through a lottery to sit in on the proceedings because the Pearl Harbor courtroom was too small. In retrospect, he said, the media should have gotten together and asked a federal judge to move the proceedings to a larger room.

One key issue was never addressed in the case: Why wasn’t there no testimony of 16 distinguished visitors aboard the sub used in court and witnessing the actions before the rapid surfacing maneuver?

The National Transportation Safety Board questioned some of them, but the Navy, which is more knowledgeable about the procedures, didn’t, Fidell said.

The NTSB investigation into the USS Greeneville collision with the Ehime Maru:

http://www.ntsb.gov/events/2001/greeneville/default.htm

Attorney Jay M. Fidell explains how the USS Greeneville

surfaced quickly into a Japanese fishing training vessel

a little more than five years ago.

Feb. 24-25, 2006

Please save this date for an important FOI conference at the William S. Richardson School of Law.

Guest speakers include former New York Times columnist Tony Lewis, Lucy Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee of Freedom of the Press, and a host of FOI experts.

Topics include media sources and military access.

You can come to one or both days free. The Feb. 24 dinner with Lewis is $60.

If you plan to go to the free lunch on Feb. 25, please let the law school know you're coming so they can have enough lunches.